|

SUNDAY EDITION May 11th, 2025 |

|

Home :: Archives :: Contact |

|

Confusion in the Oil PatchDave Cohendave.aspo@gmail.com February 11th, 2009 The only difference between a rut and a grave are the dimensions A standard story is making the rounds which goes like this: low prices and lack of investment will impair future oil production capacity. When the global economy rebounds, which could happen as early as 2010, oil prices will shoot up again as demand once again outstrips available supply. The AP's John Porretto writes don't get used to cheap oil— The oil industry is scaling back on exploration and production because some projects don't make economic sense when energy prices are low. And crude is already harder to find because more nations that own oil companies are blocking outside access to their oil fields. This line of reasoning is certainly consistent with the "peak oil" narrative, but the situation in the oil markets is not so straightforward. What will the demand for oil be over the medium-term? In order for oil prices to spike over $100 again in 2010 or 2011, demand must once again bump up against available supply, excluding some (spare) capacity that will be held back. Last week I said that I was going to defend the proposition that it is unlikely that the world oil production would ever exceed its July, 2008 peak. I realize now that I was getting ahead of myself. Instead I will use a simple model for the available oil supply and examine each term in it this week and next. 1. S(t) = PE(t)(1 - DI) + PN(t) + PSC(t) Let's examine new oil projects (the term PN in equation (1)) in light of the current oil market. Future oil demand depends on a successful reflation of the U.S. and global economy, a process that could take 2 years or more. A lot of uncertainty exists about the timing of the recovery, but considering the very deep hole we're in now and the low price of oil, it would seem to make sense to keep some new oil in the ground until economic conditions stabilize and indicators reveal some light at the end of the tunnel. The problem for new conventional oil now is not so much that companies are delaying production of oil which is in the hopper—that would actually make sense. The problem is that they will produce this new oil at a time when OPEC is cutting output and there's a glut on the world market! This behavior is shortsighted and self-defeating. Contrary to reasonable expectations, oil producers (mostly) outside OPEC are pressing forward with new oil projects everywhere you look, to wit—

Russia's oil companies are not making cuts to support OPEC although low oil prices and "lack of new greenfield projects" will take a toll on their now falling output. Among the major non-OPEC producers, only Azerbaijan appears ready to actually cut production by as much as 300,000 barrels per day. We shall see. The New York Times reported that OPEC's compliance with announced cuts was running at about 75%, an unusual display of discipline. But Bloomberg reports that compliance is currently closer to 68%, which is still pretty good. OPEC members with output quotas, all except Iraq, pumped 26.2 million barrels a day, 1.36 million more than their target of 24.85 million barrels a day, according to data compiled by Bloomberg. How long will countries desperate for revenue adhere to their quotas? Iran, Venezuela and Nigeria are in this boat. Among these, Nigeria is especially prone to fall off the wagon because they've got large oil developments coming on-stream in 2009. This West Africa producer has apparently cut production to 1.76 million barrels per day (their quota) in January, down 265,000 barrels compared with December. The cut conflicts with Nigeria's need for revenue.

Nigeria, the world's eighth biggest oil exporter, is hoping its new offshore oilfields will help boost its production as funding shortfalls and insecurity in the Niger Delta keep a cap on output from onshore and shallow water ventures... Agbami, which is operated by Chevron and Statoil in adjacent offshore blocks, is ramping up to 250,000 barrels per day by the end of the year. Akpo, which is operated by Total, will start production in April and is expected to reach 175,000 barrels per day by year's end. Will Nigeria maintain quota discipline in the face of all that potential new revenue coming on-stream? I don't think so. My doubts are confirmed by recent statements by Mohammed Barkindo, group managing director of Nigeria National Petroleum Corp. (NNPC), who believes that these and future deepwater projects are viable at only $40/barrel, which conveniently for them is also the current oil price (Oil & Gas Journal, January 28, 2009). And I'm quite sure Chevron, Total and Statoil will not object to producing the oil. Outside of OPEC, the need for immediate returns for shareholders conflicts with shrinking demand and low prices. Consider the way Chevron and ConocoPhillips have responded to a deteriorating world economy. Chevron thinks the future looks bright. Unlike some large oil companies, the company said "an excellent queue" of projects had formed, and there was no reason to change spending from the record levels of 2008. ConocoPhillips, sensibly, is worried about the future. The recession and global financial crisis are taking a toll on energy companies after several years of rising oil and natural-gas prices, and is the first of the world's major publicly traded oil companies to respond with big cutbacks... Do Chevron (and British Petroleum, Petrobras, etc.) know what they're doing? Sure they do—they're making money for their shareholders. They will probably accomplish some other things as well—

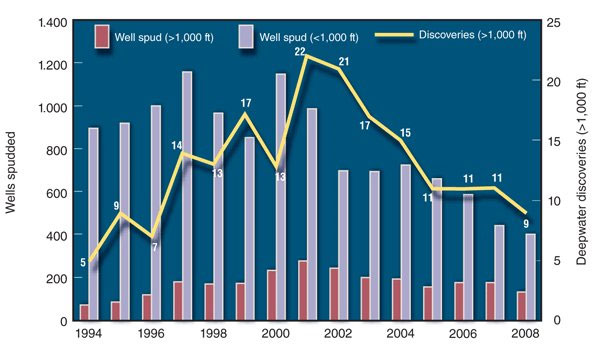

Declines in deepwater oil fields come on relatively quickly and these declines are steep and rapid once they occur. Where's the next generation of Gulf of Mexico projects (Figure 1) that will replace relatively large producers like Thunder Horse, Atlantis and Tahiti?

Yet again we see the triumph of short-term thinking and profits over longer-term survival strategies. On this view it is not so much project delays that are impairing the future as it is full implementation of current projects outside of OPEC that were begun 4 or 5 years ago when demand and prices were rising. Persian Gulf countries are not delaying planned capacity expansions, but they're obviously not going to produce this new oil anytime soon. Unlike Chevron, Saudi Arabia, Kuwait, Qatar and the United Arab Emirates take the long view. One could argue that the international oil companies (IOCs) need whatever profits they can generate to support costly exploration & production (E&P) down the road. That's nonsense. IOC revenues have been extraordinary over the last few years and E&P costs are going down along with costs for everything else during the global recession. Falling costs are not stimulating activity now but should partially offset lower prices over the next few years. The IOCs can afford new E&P. Their real problem is insufficient oil to find in the places they have access to (Figure 1). The gung-ho production policies of oil companies are counterproductive in those cases where IOCs have the ability to control output. Keeping some oil off the market right now would help stabilize prices at $70-80/barrel, the range required to support investment in longer-term oil field maintenance, future conventional projects and production from unconventional sources. Profligate oil production during the global recession will not pay dividends in the end. Contact the author at dave.aspo@gmail.com dave.aspo@gmail.comFebruary 11th, 2009 |

| Home :: Archives :: Contact |

SUNDAY EDITION May 11th, 2025 © 2025 321energy.com |

|